LUXURY BRAND MARKETING - 3

What we can learn from luxury brands. The tricks they use that you can too

For anyone new here, I’m the founder of the Pull agency. We believe that every brand has a better story waiting to be told. Our job is to find it, and help you tell it. We don’t really like talking about rebranding or re-brands. We do believe in the need to progress your brand over time.

So if you think your brand needs a stronger strategy or identity. Schedule a free intro Call.

Thanks for reading Brand Marketing for Smaller Brands. Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

This is third of three articles based on the seminal work on Luxury Brand Management – ‘The Luxury Strategy’ by JN Kapferer and V Bastein. Now this is weighty tome - a 400 page hardback - and the authors are French academics and luxury marketing practitioners. So in my articles there is an element of “I read this so you don’t have to.”

The three articles cover the three things that have intrigued me since I started working at the classical brand management house of Procter & Gamble.

2. What’s different in luxury brand marketing?

3. What can managers of non-luxury products learn from the rules of luxury branding?

So just to recap. Articles 1 and 2 identify what makes a true luxury brand and why marketing luxury is different. As the answer to both those things is quite involved I will try to simplify them here:

1. True luxury brands are the product of creative visionaries and contain codes of mythology and stories.

2. The marketing of luxury brands is different because you are not solving consumer’s problems – you are ‘inventing the dreams of the elite’.

By definition – only a minority of brands can be truly luxury ones. In reality, many are ‘merely’ fashionable or premium. So the question we will try to answer in this article is: If luxury is actually a sliding scale, are there certain luxury marketing strategies that can be applied to non-luxury brands?

If this continuum exists with say true luxury at one end, and averagely-priced branded CPG at the other, then we are talking products and brands somewhere in the middle. If you think your brand is there – read on.

ICONIC BRANDS

Based on the definition above. Luxury bands are born that way. They can’t be faked. But there are a few good examples of brands that will never fulfil the criteria to be a luxury brand. But they can benefit from some of the advantages of a luxury brand – principally category-leading margins – by adopting selected luxury brand strategies. I would describe these brands as Iconic.

Two great examples are Apple & Mini.

APPLE

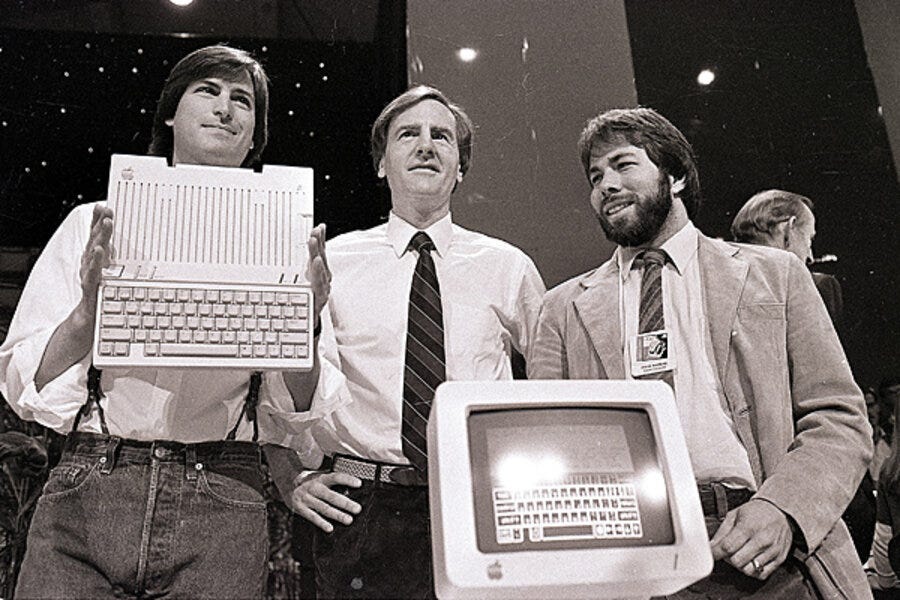

Steve Wosniak and Steve Jobs founded Apple in the brave new world of early personal computing in 1976. Their vision was almost anti-geek and anti-tech. Unlike the competition, products were designed to be easy and friendly to use, and they promoted them on mass media with powerfully emotional ads like the ‘1984’ Superbowl ad to appear as a reactionary force to ‘Big Tech’ like IBM.

Steve Jobs was ousted in 1985 by his own hire John Sculley (hired after using the immortal words: "Do you want to sell sugared water for the rest of your life? Or do you want to come with me and change the world?) Sculley had previously been VP of Marketing at CPG brand Pepsi. For the next decade Apple seemed to struggle, apparently confused by their own lineup and confined with their own operating system while beset from every angle by the widely licensed Windows OS.

What happened next is the stuff of any mythology and helped create what would be a key part of a legendary luxury brand. The exiled leader returned and order was restored. Under Jobs innovative new digital products were launched: iPod, iTunes, iPhone and iPad. In 2007 Apple’s stock value overtook that of IBM and by 2011, Apple had more cash than the US government.

So what were the rules of luxury marketing that Apple wittingly or unwittingly followed?

1. Brands must have a history and a story. It is the product of one or two visionary founders, one who was exiled and returned to save the company.

2. R&D mustn’t be consumer-led. Steve jobs was notorious in his disdain for the role of market research in innovative consumer tech. “The consumer can’t tell you what it should look like – we have to.” This could have been Enzo Ferrari speaking.

3. Indifference is bad. You need lovers and haters. Although Byron Sharp would probably protest that Apple’s brand loyalty is exaggerated. There don’t tend to be many people on the fence. Many buyers have an almost religious fervour about the brand. Non-buyers see it’s superiority as over-blown and not worth the premium.

4. Remain elitist. The Apple experience is segregated and tightly managed. Whereas you can buy a new PC on eBay, Apple stores showcase Apple products and display them like luxury goods. Apple products tend not to play with the mainstream. This helps keep buyers in the walled-garden, but also makes the experience feel special.

5. Premium pricing. Apple products command a premium. Because they are not licensed versions of the same thing like a PC or Android phone, they also follow another rule – don’t invite comparison – which supports the premium pricing.

6. Never sell. Normal brands struggle endlessly with the ‘long and the short of it’. Constantly tempted to forgo future demand (through brand-building marketing) to harvest current demand through performance marketing, sales and discounts. Apple only focuses on long-term brand-building and future demand.

7. Refined and artistic communication. Apple has been burnishing an increasingly sleek and well-designed look that is consistent across all products, all brand assets and all channels. It targets influential designers, artists and musicians for collaborations and publicity.

8. Consistency and simplicity of identity. When combined with the lack of selling above, it has created an unmistakable identity that is easy to recognise, is aesthetically pleasing and encourages emotional attachment. (in my update on Brand Architecture I remarked how Apple in my view has morphed into a new brand archetype – the Omnibrand’ where iPad, iPhone etc. are no longer sub-brands as they were, but simply Apple products under the one Apple brand).

MINI

Automotive M&A is littered with the corpses of brands that were probably misunderstood or over-rated by acquirers. Many thought that BMW’s chairman Bernd Pischetsrieder was suffering from an emotional attachment to a sketchy set of faded automotive brands – many no longer in production – when he eyed-up Rover in 1994, the remnants of a patchwork quilt that was previously British Leyland. It was framed by his detractors as a mis-placed and sentimental attachment to the dated engineering and wood and leather interiors of English cars that reminded affectionate Germans of Britain’s historical automotive past.

But he was eyeing a prize that came in the Bagatelle of brands – Mini – describing it as “The only lovable car on the road“. The Mini was the innovative brainchild of Alex Issigonis (by an extraordinary coincidence – a first cousin once-removed of Bernd Pischetsreider). Born out a fuel crisis, Mini was far from a luxury product, but it was a very clever one. With simple, radical and inexpensive suspension, a wheel at each corner, front-wheel drive and transverse engine, the packaging was ingenious. It also looked distinct and modern.

People loved it, and the Mini earned an affection rarely accorded to a car. The shape had evolved gradually over it’s more than 40 years in production (see Porsche in Luxury Branding 1), but BMW knew it had to move the Mini on or let it die. In what is often cited as a copybook evolution of an acquired brand (both design and brand), BMW launched a new version of the Mini in 2001. They respected the heritage. The new Mini was 60cm longer than the original, but faithfully retained its proportions. Global sales have remained strong ever since, even as the Mini has become electric while other ICE-engined models from competitors have died, and new EV-only brands born.

So what rules of luxury marketing did BMW wittingly or unwittingly follow with Mini?

1. R&D mustn’t be consumer research-led. The new Mini wasn’t cliniced into existence or designed by a committee (see Lexus in Luxury Marketing - 1).

2. A strong geographical anchor to its beginnings. Minis are still produced where they first were at Oxford in England. The rear light cluster subtly mimics the British Union Jack flag.

3. A cultural anchor. There are still echoes of the liberated 60’s birth of the Mini in the brand. The Britain of the mini-skirt, The Beatles and Brit-pop scene.

4. Customisation. Almost no two Minis look alike thanks to high levels of customisability that is only normally on offer with premium and luxury car brands. This allows a high level of individualisation and expression to owners.

5. A singular iconic outline (like the Porsche 911) that has changed but remained the same.

6. A relationship to art. The first Mini became on of the iconic shapes of it’s century, adopted, painted and decorated by artists across the globe. This led to partnerships with FIAC (Foire Internatioanle de l’Art Contemporain) Apple Expo, Paul Smith, Kate Moss etc. Minis are the unquestioned stars of the celebrated 1969 film ‘The Italian Job’, re-made in 2003 with new Minis.

7. Exclusive distribution. BMW wisely decided Mini should have its own dealership network to preserve its particular brand persona and not let it fall into a ‘cheap BMW’ persona. On the other hand, almost everyone buying a Mini knows it is ‘built by BMW’.

8. A community of believers. With similar levels of affection that the original model enjoyed. The attachment to the brand today is still emotional, and results from a ‘lovability’ that the brand has long cultivated, and consistency in model design, look and brand tone of voice. Mini is almost alone today in using humour in advertising for cars.

So how can brands benefit from deploying some of the set of luxury brand strategies?

What both Apple and Mini also have in common is profitability. Apple has earned a position as the world’s most valuable brand at an almost bewildering $1.2 Trillion value today. A huge amount of that value comes from not just its revenues, but its far higher than average margins. That’s what following some luxury marketing rules gets you – some of luxury brand’s margins – and when you multiply that by Apple’s revenues. . .

Mini in its first incarnation was popular – it sold in millions across the world, but never made any money. BMW’s version however, leveraging and cherishing the brand’s strong heritage, but bringing their own engineering and build know-how has been profitable throughout their ownership – despite a very turbulent global automotive market.

So to know how to pick the rules of luxury marketing that suit your brand, first you need to know what a luxury brand is. Then you need to understand the rules. Then you need to pick the ones that work for your brand. Now you know.